Levers of Social Change

Mechanisms that shape society

“The world is awful. The world is much better. The world can be much better.” - Max Roser

I recently made a surprising discovery that people have learned the same few lessons in pursuit of making the world a better place. This post is inspired by this thought-provoking podcast episode by FED, a non-profit working towards expanding economic liberties in India. A lot of this information may be enlightening for others who, like me, were born after the economic liberalization in India.

However, as someone interested in social movements and moral progress, I was fascinated by another realization. Regardless of your endeavor — be it fighting for more economic development, a sustainable future, or better welfare for humans and animals — the same few themes, levers of change, and pitfalls stand out.

I think broadly there are three levers of change:

Culture sets what people do by default

Policy sets what people are incentivized to do

Technology sets what is possible to do at all

Culture

Most of us know how powerful culture is, we’ve felt it. So many of the things we do are really just because of culture. From trivial things like how we greet each other or what colors we prefer to even the big things like our attitudes towards risk or what diets we follow. So many times it feels like a choice we’ve made but can’t seem to pin down the reason we do it.

One of my favorite examples of the power of culture is vegetarianism in India. I wasn’t raised a vegetarian, but I knew many friends who were vegetarian growing up. In most cases, I found the reason for their vegetarianism strange. It was exceedingly rare for any vegetarian I met to cite concern for animals, ethics, or anything intrinsic to them as one of their primary reasons. Apart from the odd person who was motivated by morality or disgust of handling meat, the overwhelming majority usually cited allegiance to their familial practices, rituals, religion, and culture as their only motivation. Back then, as a teenager who made my whole personality about challenging the existing norms, I found such justifications perplexing — and yet it made me realize the power of culture quite early on.

However, I don’t think I’m special to have noticed the power of culture. As they discussed during the podcast, this seems to be the go-to lever for most groups trying to change the status quo of what matters to them.

Many groups start out with the hubris that the Sisyphean task of changing culture is most definitely surmountable, and that they are best poised to make it happen. In fact, most spend their entire lives like Sisyphus attempting to roll the stone of culture up the hill only for the stone to roll back down. Of course, as the famous existentialist philosopher Camus points out, “One must imagine Sisyphus happy”; I too think most people engaged in trying to change culture are actually happy with their act of resistance, and with their attempts to change culture — sometimes even to the detriment of the outcomes that they actually care about. I’ve been there too and I’ve written about some of my lessons here:

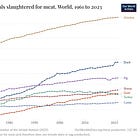

The thing about culture though is that no one person or community can really tame it or control it. Things change! Going back to my previous example of vegetarianism, among other factors, the grip of culture on this issue has weakened in India. What I’ve experienced personally through anecdotes also lines up with the data. The per capita meat consumption is rapidly increasing.

Raising awareness about important issues, especially those outside the Overton window, is most definitely an uphill battle. Even still, culture remains a powerful lever, for you never know when the Overton window shifts or what actually gets it to move.

Policy

So many things we pursue in our day to day lives are the results of broad scale incentives at play. Policy, for example, determines what we do for a living (nationwide industrial policies), how much we work (labor laws), where we choose to live (zoning policies), or what we choose to eat (food subsidies).

Since this is such a powerful lever, it is also a closely guarded lever of change (“downstream of culture” - as they mention during the episode).

I still believe policy is a more realistic pathway for issues where there’s majority support — such as ending extreme poverty or reforming factory farming — even if individual behaviors don’t align with these objectives (and perhaps never will).

The thing to realize here is that policies don’t just determine these first order effects of what is or isn’t permitted, they also in fact help shape the incentives that power people.

Another aspect of this lever is that good policies are not intuitive to us most of the time. Policies with the best of intentions can still lead to disastrous outcomes. In economics this is sometimes referred to as “The Cobra Effect”. I found the origin story of this term interesting:

This name was coined by economist Horst Siebert in 2001 based on a historically dubious anecdote taken from the British Raj. According to the story, the British government, concerned about the number of venomous cobras in Delhi, offered a bounty for every dead cobra. Initially, this was a successful strategy; large numbers of snakes were killed for the reward. Eventually, however, people began to breed cobras for the income. When the government became aware of this, the reward program was scrapped, and the cobra breeders set their snakes free, leading to an overall increase in the wild cobra population.

Technology

Technology has consistently enabled a small group of committed individuals to dramatically change the way societies work. This is, after all, what most budding social movements aspire to achieve. What surprises me about this lever is that society leaves it largely unguarded.

For instance, prior to the invention of the printing press, books were expensive and education was a privilege reserved only for the elites. It was the invention of this new technology that actually helped usher in a new era of education and level the playing field. In the modern age, the same argument could be made for the invention of the personal computer, the internet, search, phones, or AI. Every one of these tools has further democratized access to information, freeing us from the limited scope of ideas that were previously constrained by the location of our birth. As many economists have argued, the story of human progress and has mainly been the story of technological progress.

There's nothing new about discounting technology. In the year 1798, the economist Malthus famously predicted that population growth would outpace food production, leading to inevitable cycles of famine, disease, and war. His name is now a pejorative: "The Malthusian Trap”. Of course, his predictions couldn’t be further from the truth, as just this week Our World in Data posted how the opposite has been true for the last half century.

I am most optimistic about the impact of technology on society in the long run. I am positive that technology can help us figure out how to give people what they want without the associated harms or externalities.

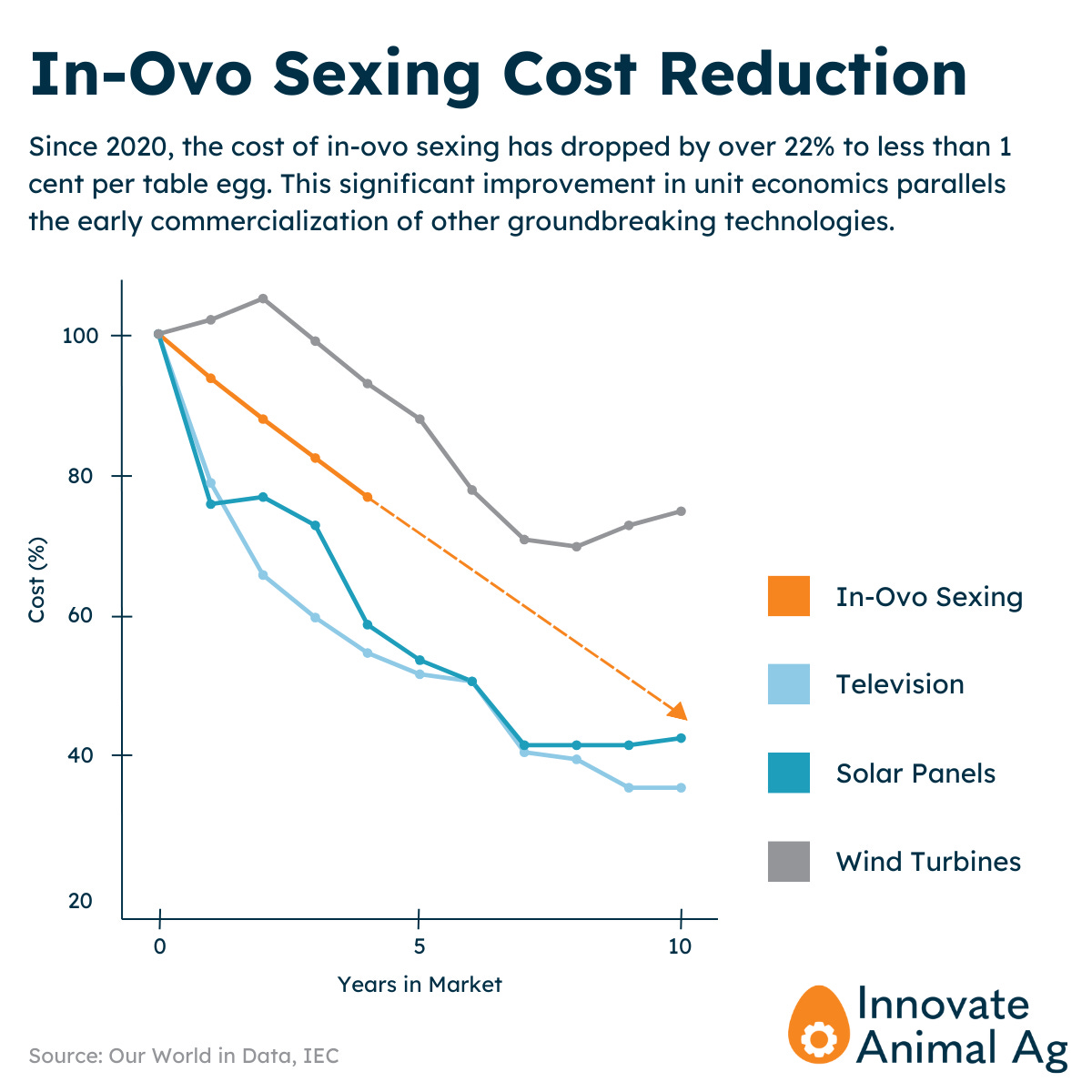

The most iconic demonstrations of technological progress have usually been straight lines on a semi-log graph. These are pictures compressing a thousand small improvements. They show how you can make exponential progress on some metric of productivity in a linear amount of time, which is an incredible feat of human ingenuity. Here’s one such graph about a technology that I’m really excited about: in-ovo sexing. This tech helps us eliminate the standard practice of male chick culling in the egg industry.

Caveats to Human and Technological Progress

That being said, conservatively, hundreds of trillions of sentient beings have paid the price for human progress, and this is unlikely to change in the near future. However, I remain optimistic. It took me an embarrassingly long time to realize that every human isn’t just a stomach but also a brain. The more humans flourish, the more talented people there are to change culture, draft policies, and invent new technologies to address the world's most pressing problems.

Speaking for myself, being able to take care of my basic needs (as well as my family’s needs) always superseded any other global issue. Similarly, apart from the ~15% of the population that lives in the developed world, very basic necessities still motivate the majority of human existence. It's nearly impossible for even the best messages or policies to make someone care about issues like climate change or animal welfare when their primary concern is how to feed and house their family.

Closing Thoughts

What about the interplay of these three levers? New technology has the potential to change culture, which can then help shape policy. A famous example to this effect is the discovery of fossil fuels, which helped humanity move away from whale oil as a primary source of fuel for lighting. This also changed our culture from being whale killers to being conservationist whale watchers, which eventually led to whaling bans almost everywhere.

hu·man: of or characteristic of people’s better qualities, such as kindness or sensitivity.

Being compassionate is literally in our name. I am positive we can advocate, legislate and invent our way towards a kinder and better world.

However we get there, I do feel that, civilizationally, the best thing we can do is embed this more deeply into our culture:

"Being compassionate is literally in our name. I am positive we can advocate, legislate and invent our way towards a kinder and better world."

Creating a community of purpose-driven, open-minded, and compassionate change makers would likely sustain the technological, social, and policy-growth to actualize humanity's potential. Great read!